3 1/2 Years -- The "Crack House Law"

Drug War Paves Way for Urban Renewal

After sleeping a few hours, he drives from his one-acre rural home in nearby northern West Virginia to dutifully open Cartwright's Recreation Center six days a week from 1 to 4 p.m. It had always been a low-income Winchester, Virginia neighborhood, and the Center built by Tony's father in 1969 was where people gathered to eat a burger and fries, socialize and shoot a game of pool. In its hey-day the Center filled with General Electric workers after shift, and opened on the holidays to provide free dinners and companionship for those lonely or hungry.

The neighborhood had changed, and Tony was glad he lived 35 miles away from it. Outsiders posed new threats and violence around the drug trade. Tony's 75-year-old father couldn't manage deteriorating health, coupled with escalation of drug traffickers exploiting the "old man's recreation center".

This area of Winchester had been called The Block as long as anyone can remember -- an eight-block area, the aging Recreation Center sat in the middle of it for almost 30 years. Allen Cartwright's 1960s' dream of a community space evolved with harder times into a neighborhood nuisance. The sale of illegal drugs was a long-standing community problem, but the police routinely avoided confronting open-air drug markets throughout The Block. They would however, come in to set up buy and busts. Tony urged his siblings to help him convince their father to close the recreation center entirely.

The compromise was to reduce the Center's hours to afternoons, closing before dark. Within this whirlpool of pressure, Tony drove to the Center wishing he could spend more time with his wife, Sharlene, in their quiet home on a West Virginia hillside.

Unknown to Allen or his son Tony and most business owners of real estate, is that in 1986 the "crack house" law went into effect, making it a federal offense to:

(1) knowingly open or maintain any place for the purpose of manufacturing, distributing, or using any controlled substance; (2) manage or control any building, room, or enclosure, either as an owner, lessee, agent, employee, or mortgagee, and knowingly and intentionally rent, lease, or make available for use, with or without compensation, the building, room, or enclosure for the purpose of unlawfully manufacturing, storing, distributing, or using a controlled substance.

The Crack House Law remained unchanged on the federal books until the turn of the 20th century, when young white people caught on to dancing without having to pay a live band. Electronic music lured them in droves to hours-long dance parties. The dancers called them 'Raves;' Sen. Joe Biden called his 2002 Crack House 'clarification' the Rave Act, and Allen and Tony Cartwright fell victim to the muddied statute.

Biden insisted his bill would not hold "the owners and the promoters responsible for the actions of the patrons," and went further, "We know that there will always be certain people who will bring drugs into musical or other events and use them without the knowledge or permission of the promoter or club owner." Tony's 11-page Plea Agreement of January 11, 2007 illustrates very well that then-Senator Biden was wrong in assuring the law wouldn't unfairly play out in practice.

After police raided and closed the Center in September 2006, Tony, as manager, was threatened with 10 years to life in prison if he went to trial and lost. With his ailing father under pressure of possible indictment, Tony, as the saying goes, "took the rap." On August 12, 2007 the 47-year-old -- with no criminal history -- was sentenced to 41 months in federal prison.

Most of the 28 codefendants in this cocaine-base, drug conspiracy pled guilty, as do about 97 percent of accused drug law violators. Why such a high rate? Because federal prosecutors have enormous, unchecked power to manipulate, coerce and threaten defendants. Such power relies on clouds of secrecy, fact and charge bargaining, count stacking, bait and switch deals, unreliable informant testimony, real offense sentencing practices, and other coercive prosecutorial options not subject to inspection or regulation. A paid or public defender has nothing but "The Plea."

The United States Sentencing Commission is empowered by Congress to monitor and regulate the entire federal sentencing process. It can't, and admits this candidly throughout its 15-year Study published in 2004, documenting the shift of sentencing power from judges to prosecutors through manipulation of charges, sentencing tables, overwhelmed defense counsel and defendants.

In Tony's case the U.S. Attorney cut through such complexity using plain language: go to trial, Tony, and so will your father. Accept our offered plea agreement, your dad's charges will be dismissed, and instead of a possible 10-to-life you get a small sentence in a federal camp. These proceedings are off the record, and on the record anyone taking a plea agrees minimally, like Tony, to the following waiver of rights to:

* plead not guilty and persist in that plea

* a speedy and public jury trial

* assistance of counsel at that trial and in any subsequent appeal

* remain silent at trial

* testify at trial

* confront and cross-examine government witnesses

* present evidence and witnesses in one's own behalf

* compulsory process of the court

* be presumed innocent

* a unanimous guilty verdict

* appeal a guilty verdict.

Most other codefendants in Winchester, Virginia's highly-publicized conspiracy were 'locals.' Two went to trial; one 'kingpin' got life, the other absconded, and local citizens got the most prison time. But the government wasn't done.

Though Tony and his siblings believed they could block the U.S. Attorney's move to seize the Cartwright's property under civil asset forfeiture laws, they offered to donate it to a local Boys and Girls Club. The decision was applauded by community leaders and residents of The Block. That should have helped reduce Tony's sentence, but according to records the sentencing judge ignored the offer.

In his January 11th guilty plea Tony agreed "to cooperate fully in the forfeiture of this property." Federal law provides that property used to facilitate drug trafficking can be forfeited to the United States, unless the owner didn't know about it or did his best under the circumstances to stop it. For Tony and his father those 'circumstances' included threats of bodily harm from armed traffickers in the neighborhood. Such threats and intimidation, say experienced attorneys, should have been enough for the judge to keep Tony out of prison, if not fully exonerated.

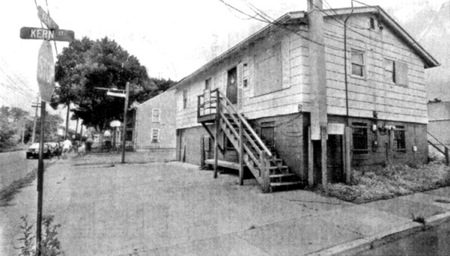

Though protected by 'grandfather rights,' Allen Cartwright Sr., as sole owner of the Recreation Center property, agreed to the forfeiture in April 2008 for a payment of $11,000, according to court records. By September it was sold to Winchester's Economic Development Authority for $79,900. According to media reports the "EDA will work with city officials and North End residents to make plans for the property's future."

Will that future be low-income housing, a church or a revived Rec Center that offers free meals and rooms for hungry people and seasonal workers, as the Cartwright Family did faithfully year after year? Or is it a successful advance toward the goal of The Block's gentrification by developers? Are drug forfeiture laws used to further the "noble goals of gentrification?" And where do the poor go?

Such questions aren't raised in legal proceedings, nor this one. Why is drug trafficking still a problem in and around the long-closed Rec Center? The DEA and local police rejoiced with the closing of the Center and promised Winchester citizens they had rid the Block of the drug problem.

Why should a good man who loved and labored a lifetime for his father, his family and community, be an imprisoned scapegoat for the failures of law enforcement officials, discriminatory drug policies and the upscale designs of City planners?

Reflecting confidence in Tony Cartwright's integrity, and looking to restore some of the Cartwright's losses, his most recent supervisors at National Fruit of Winchester, VA have offered to re-hire Tony for his old job after his projected 2010 release.

Update: Sharlene Cartwright wrote February 15, 2009, "I've been diagnosed with acute ALL leukemia." Easily curable in children, she says it's the opposite for adults. "I will have to go through extensive chemotherapy and radiation treatments for 4 to 6 months; while in remission, I'll be given a bone-marrow transplant." Though her sons are with her and supportive, shouldn't the BOP release Tony immediately to serve as her primary caregiver in coming months of recovery -- in which she'll eat like a baby, live under a no-contact bubble, and rebuild her immune system? "My nieces and son are going to write President Obama to see if anyone will listen to get Tony released somehow."

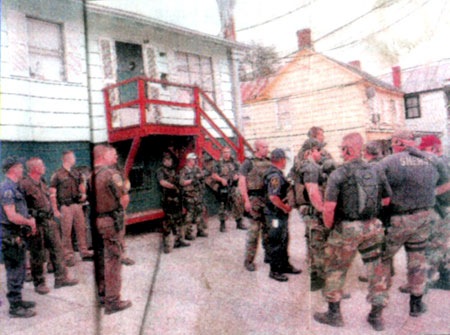

Law enforcement officers gather at Cartwright's Recreation Center at Kent and Kern streets in Winchester last September during an investigation into drug activity in the area. Cartwright's manager Tony Augustus Cartwright pleaded guilty Thursday to making the facility available for cocaine distribution. (photo Jeff Taylor / The Winchester Star, 7/13/2007)

The building that formerly housed Cartwright's Recreation Center at Kent and Kern streets in Winchester has been siezed by the U.S. government. A real estate agency has listed the propertry with a price tag of $79,900. (photo Scott Mason / The Winchester Star, 7/2/2008)

More about Tony Cartwright

I am writing you this letter on behalf of my good friend Tony Cartwright. I met Tony at General Electric about 8 years ago. He was my superintendent at nights, and not only that, he was like a father figure. He kept me straight, helped me out with money, and kept me in a job. Because while I worked nights I went to school during the day. So I had a difficult time working, but Tony helped me right along.

And me being from West Virginia raised to hate the blacks. Something about Tony changed that. I have a lot of respect for the man. And if it wasn't for him I wouldn't be here where I am today. He has helped a lot of people, and always been kind and caring to other people. My feelings about the man is that he is no drug dealer, user or criminal. But a good American.

He is a good man, and I would stick my 100 per cent country neck out for this man that is being wrongly accused. And I would stand with this man anywhere.

Now sorry about my writing and spelling. But this letter is the real deal; it's not perfect, and neither are we, but that Tony is pretty damn close. -- Handwritten letter to federal judge Conrad at Tony's August 13, 2007 sentencing

Tony is the youngest brother and as such the responsibility of caring for my parents fell to him. He was always agreeable and went out of his way to avoid confrontations and conflict, internal and external to family affairs When my father required knee surgery in February 2005, this with the mental illness complications, pushed Tony to suggest we close the recreation centerAs a result of this case, I can say we all wished we had agreed with Tony on closing the place. But little brothers are often not heard, and I truly regret my part in not hearing my brother.

Out of respect to my brother Tony, we are finally listening to him and have agreed to give the property to the Boys and Girls club of the community. Tony has always had a real concern for the welfare of the children living near and around the recreation center. He has coached many of the neighborhood childrlen in basketball alongside his two boys, and I have personally observed him providing basketball shoes for some who had none. Tony believes that by donating the property some level of good will come out of this difficult situation. After his emotional and persuasive appeal, we have finally listened to my younger brother. -- Excerpts from Allen W. Cartwright Jr's August 7, 2007 letter to sentencing judge Conrad

When my late husband passed away, I worked at Food Lion for awhile. Then I got a job as a temporary at GE where I worked for about two years. On Thanksgiving and Christmas, GE would give out turkeys to all of the employees. Well, that did not include the temporary service workers from Manpower of which I was one.

Tony went to the head office and talked to the plant manager because he said it was not right to give everyone a turkey for the holidays and not give to the temporaries who worked harder and made less money than the regular employees. He told the plant manager the temps need this more than we do. He convinced the plant manager to give out turkeys to everyone who had worked there no matter if they were from a temp service or not. So they did.

We did not know Tony was responsible for this until much later when someone else told us. He was just that kind of person. Always was and always will be. Like I said: he is the kind of person we all wish we could be. -- Excerpts of correspondence from Sharlene Cartwright, 2008