Determinate Sentencing's Quandary

By the time law students and criminal justice majors are hitting the books, and finding these summertime messages about 'real offense guideline sentencing,' exploring the way that the federal government's broad application of uncharged, even acquitted conduct can ratchet up a sentence, complete with stale criminal histories, tales of informants, etc and all — I'll be sleeping under the stars and kayaking in a nearby river.

I want to leave readers with something meaty in my absence. Ordered from public archives, the LEAA Library, a former prisoner volunteered to scan it, and we've made it available on our website. It's called "...WE ARE THE LIVING PROOF..." The Justice Model for Corrections and was authored by David Fogel in 1975. Dr. David Fogel was an Illinois Correctional Official, one of a successive few corrections officials to promote administrative justice models, now called 'determinate sentencing' in reality, but called 'Sentencing Guidelines' in practice.

WE ARE THE LIVING PROOF is 328 pages, and 33 years old, but crucial academic history as to how sentencing revolutionized in 1984. The LEAA library, or collection entire is likely significant because as anti-prison abolitionists of the day warned — LEAA, the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration was to police and prison officials, what the pentagon is to the military today. Yet the author, David Fogel was a self-proclaimed 'fortress prison abolitionist' -- and the plot thickened for me because I'd long had a hunch that 'progressive' ideas went real bad, and having a brother 19 years down on a guideline (wink, wink) sentence of 27 federal years, I read Fogel's work with far too much fascination. And reading it, I kept thinking about all the prisoners who've wondered who cooked up parts of this mess we are in, and legal students, and advocates might appreciate the thought and sentiment behind what has become an entirely revolutionized federal sentencing system.

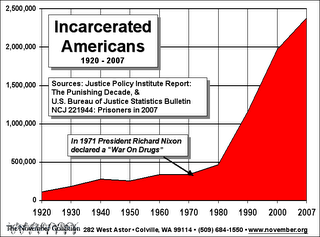

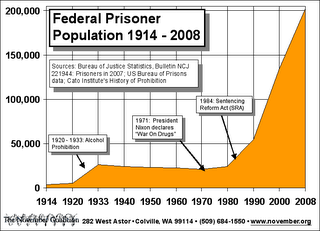

In some fairness to Fogel, he warned that all of his ideas would have to be implemented, and if piecemeal adoption took place -- would only create what is easily illustrated in alarming ease -- the United States has a "carceral crisis,' of epic proportions.

One of Fogels goals was to abolish parole and have fixed sentencing -- that this system would respect the keepers and convicts. Writing of and to his critics, he wrote long into his manuscript:

Even assuming the relevancy of our claim that the rationalization of parole along lines of a punishment-deterrence-justice model could bring more safety, sanity and fairness to prison life, some have argued: "Why mess with the system?" Some critics reason that even if the present anomie in sentencing and parole appears to be unjust, most prisoners average only a two year plus stay; and the more the appearance of unfairness is exposed, the more tightening up will be legislated. This might, in their view, bring more convicts into the system and keep them longer. Therefore, modernization may contain the seed of an unintended consequence which could operate against the cause of lower numbers of prisoners with relatively shorter average stays as compared to actual sentences. Hence the rationale becomes: "leave it alone, you can't really affect the onerousness of prison life anyhow, and you may open up a Pandora's Box for conservative legislators which will produce draconian prison stays (actual) rather than merely the semblance of long sentences as we have now." This is not unattractive. It is even a bit seductive. But it is not convincing on several grounds.

Fogel goes on to explain that high levels of imprisonment would cost too much, and legislators who promoted harsh sentencing would easily be voted out of office. Yeah, this smart man -- esteemed and highly regarded in his field, could never have been more wrong, and critics more prophetic.

This old writing, in support of fixed, determinate, mandatory sentencing, called guides or otherwise should prove interesting for lots of people intent on spending time in their futures creating new federal criminal justice laws and policing policy.

When we ask for returning parole, or forms of earned, early release, we need to know that we confront more than sentencing law, we confront sentencing philosophy, too.

Labels: Real Offense, Relevant Conduct, US Sentencing Guidelines